LaRhea Pepper has been marketing organic cotton for 30 years. And by marketing, I don’t mean just selling, I mean the whole gamut. She pays attention to all aspects of the product, in addition to promotion, distribution and price. I first met her in 1992 when she was just getting started. She was living on a fifth generation cotton farm south of Lubbock, Texas, and had recently convinced her husband’s brothers to move to the area. She’d convinced the three Pepper brothers than she could sell organic cotton if they would produce it.

They’d grown up on an 800 acre farm which had plenty of water (4000 gallons a minute). Their father passed away too early in 1988. Farming conventional cotton, “we could see zero by 1991,” Carl Pepper says. The oldest brother has studied accounting, ran the numbers and told Carl he could borrow $250,000 for $15,000 profit given conventional cotton’s costs and return. He and his wife said, “That’s nuts” and started looking for options.

Meanwhile, brother Terry had married LaRhea and begun farming in her home county on the High Plains of Texas. Borden County has about 600 people, two cafés right now and a bunch of farms. No banks, no grocery stores, no feed stores. Her grandparents wanted to retire and turn over their land to Terry and LaRhea. Terry and LaRhea took the opportunity and began raising cotton and kids. After the kids were in school, LaRhea and Terry decided to move toward organic cotton now that LaRhea had time to market it. They grew their first organic cotton in 1991, took it to a mill to be made into denim. LaRhea had sold the fabric by the time the mill had spun it into yarn, woven it, finished and delivered it.

About that same time (1991), LaRhea’s uncle decided to retire. He had 800 acres and a farmhouse and offered it to Carl and his wife. His accountant brother said on this land, they could borrow $60,000 for a return of $40,000 and liked those odds better. “The Good Lord provided us a place to go,” Carl says.

Things didn’t look quite so propitious when they were moving in during a January 1992 snowstorm. Carl’s wife refused to let him unload her boxes and informed him she was leaving shortly thereafter. In due time she relented and they were blessed with a dollar per pound for a quarter section of organic cotton. They were chopping in high cotton to use the old Southern phrase meaning living high on the hog.

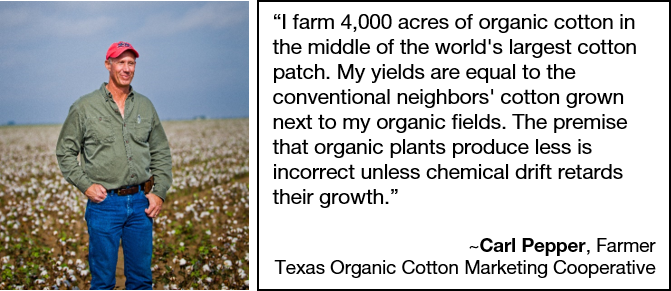

Carl says his older brother Kelly warned him to set some of the profits aside because “this country can get tough. By the end of the 90s, Carl had used up his surplus funds and realized his brother was right. By then, they had created a strong presence in the organic market by organizing the Texas Organic Cotton Producers Cooperative with Kelly as President. The Co-op has 20 organic growers and 20,000 acres of organic production. Carl has 3600 organic cotton acres and grows another 400 acres for his sister in law, LaRhea.

Most of the growers are in Borden county on the southeast edge of the Ogallala aquifer. The aquifer and the flat land above it, end at the Caprock formation with a drop off of 1000 feet to the rolling lains of central Texas. Cropland turns into cattle grazing land at the Caprock.

If you want to learn about resilient farming in a pretty forbidding country, go visit Carl Pepper.